Available Languages

- Consultez cette page en FRANÇAIS

- Consult this page in ENGLISH

Analysis by Classification

Connaître, penser, c'est classer.

Georges Clémenceau

The human mind seems to lean naturally toward classification and hierarchy (or anarchy, which boils down to the same thing) [...]

G. Girard, R. Ouellet et C. Rigault, L'univers du théâtre

1. ABSTRACT

A unit belongs to a class – is one of its elements – if it corresponds to the definition of the class, i.e., if it possesses the defining properties (or features) thereof; in this sense, an analysis by classification is always a comparative analysis, since it is a matter of comparing the defining features of the class and the defining features of the potential element. Two main forms of analysis by classification can be performed on a semiotic act (text, image, etc.): (1) classification of the act, which consists in classifying the whole of the act into a particular class (for example, into a genre acting as a class) and (2) classification within the act, which consists in classifying elements that make up the act, whether they are (2.1) "real" elements (e.g., classifying each sentence of a text as affirmative, negative, interrogative, etc.) or (2.2) thematized elements, represented in the content (in the signifieds). The latter kind of analysis will be the focus here. This type of analysis by classification consists in examining the object under analysis – and interpreting its causes, modalities, and the effects of its presence – to discern a thematized structure of any complexity made up of (1) encompassing classes, (2) encompassed classes, and (3) elements belonging to these classes. To give an example, Mallarmé's sonnet, "Her Pure Nails" ("Ses purs ongles très haut dédiant leur onyx") deals with at least three classes of absence: absence in the ordinary sense (elements: the empty parlor, oblivion, etc.); absence through destruction (elements: the ashes of the funerary urn, the deceased, etc.); absence through unreality (elements: the mythological characters, the dream, etc.). Absence, then, is an encompassing class, and each of the three subclasses of absence is an encompassed class. Once it reaches a certain degree of complexity, a classification is usually represented by some sort of visual diagram, e.g., set-notation graphs or a tree diagram.

This text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided the complete reference is given: Louis Hébert (2011), "Analysis by Classification", in Louis Hébert (dir.), Signo [online], Rimouski (Quebec), http://www.signosemio.com/analysis-by-classification.asp.

An updated and extended version of this chapter can be found in Louis Hébert, An Introduction to Applied Semiotics: Tools for Text and Image Analysis (Routledge, 2019, www.routledge.com/9780367351120).

2. THEORY

2.1 OVERVIEW

2.1.1 FOUR COGNITIVE OPERATIONS

Consider four major cognitive operations and the forms of complex analysis rooted in them:

1. Comparison: a particular observing subject, in a particular time frame, establishes one or more comparative relations (identity, similarity, opposition, alterity, metaphorical similarity, etc.) between two or more objects.

2. Decomposition: an observing subject, in a particular time frame, identifies the parts of a whole. The reverse operation is composition, which is to envision the whole rather than the parts (to not "see" the sugar and the eggs in the meringue). Decomposition can apply to a physical object: the object "knife" = blade + handle + rivets, or to a conceptual object: the signified 'knife' = the semes /utensil/ + /for cutting/ + /equipped with a blade/, etc. Decomposition can be physical-cognitive, such as taking a knife or a chair apart (then we can call it disassembly or conversely, assembly), or simply cognitive, as in mentally identifying the parts of a knife without actually taking it apart.

3. Typing (or categorization): an observing subject, in a particular time frame, relates a token (this particular animal) to a type (a dog), i.e., a model, of which it is a manifestation, a more or less consistent and complete emanation.

4. Classification: an observing subject, in a particular time frame, relates an element (e.g., a black marble) to a class (black marbles). Classification can be physical-cognitive (sorting the marbles by color) or just cognitive (relating a particular marble to its set). Later we will cover how to distinguish a class from a type and a token from an element.

The last three operations are similar in that they bring together including forms (whole, class, type) and included forms (part, element, token). In addition, classification and typing are forms of comparison. That is, to determine whether a unit belongs to a class (i.e., is one of its elements) one compares the defining properties (or features) of the class (e.g., vertebrate creature) and those of the potential element (this animal is indeed a vertebrate). To determine whether a unit belongs to a particular type, one compares the properties of the type (e.g., a romantic text is written in the first person, expresses emotional intensity, etc.) and the properties of its potential token (this text has the properties of a romantic text, so it is a romantic text). Lastly, the same phenomenon may be seen simultaneously from the standpoint of all three operations: decomposition (this whole-word is made up of these parts-letters), classification (this element-word belongs to the class of nouns), and typing (this token-word is a manifestation of the type-noun).

2.1.2 THE MEANING OF THE WORD "CLASSIFICATION"

The word "classification" designates: (1) a cognitive operation; (2) a single product thereof (classifying a particular element in a particular class); (3) the more or less complex structure built from more than one single classification (e.g., a taxonomic typology of the animal species, or a typology of textual forms); and lastly, (4) a form of analysis.

We can distinguish two main forms of analysis by classification to be performed on a semiotic act (text, image, etc.): (1) classification of the act, which consists in classifying the whole of the act into a particular class (for example, into a genre acting as a class) and (2) classification within the act, a local classification which consists in classifying elements that make up the act, whether they are (2.1) "real" elements (e.g., classifying each sentence of a text as affirmative, negative, interrogative, etc.) or (2.2) thematized elements, represented in the content (in the signifieds), e.g., the forms of friendship present in a novel. A global classification [overall classification] necessarily uses one or more local classifications. For example, to verify whether a poem is a romantic poem, one would check to see whether the main romantic themes are present (the first person, intense emotion, etc.). But a local classification can be autonomous and not target an overall classification of the text. For example, one might classify each sentence in the text as affirmative, negative, interrogative, etc., without necessarily aiming to classify the text overall as an affirmative text, for instance, because the sentences of that type are preponderant.

Next, we will examine the classification of thematized elements. This type of analysis by classification consists in examining the object under analysis – and interpreting its causes, modalities, and the effects of its presence – to discern a thematized structure of any complexity made up of (1) encompassing classes, (2) encompassed classes, and (3) elements belonging to these classes. To give an example, Mallarmé's sonnet, "Her Pure Nails" ("Ses purs ongles très haut dédiant leur onyx") deals with at least three classes of absence: absence in the ordinary sense (elements: the empty parlor, oblivion, etc.); absence through destruction (elements: the ashes of the funerary urn, the deceased, etc.); absence through unreality (elements: the mythological characters, the dream, etc.). Absence, then, is an encompassing class, and each of the three subclasses of absence is an encompassed class.

Encompassing/encompassed is a relational status, and is therefore relative and has no absolute value. So a class B may be encompassing relative to a class C, but encompassed relative to a class A. Not to mention that the roles can be reversed: class B which encompasses class A can become encompassed by it (an example will be given later). The relation between an encompassing class and its encompassed classes is inclusion (e.g., the class of mammals includes the class of canines). The relation between an indexed element and the class(es) in which it is indexed (from most specific to most general) is membership or indexation (e.g., between a particular dog and the class of canines).

2.1.3 THE COMPONENTS OF A CLASSIFICATION

To be precise, listed below are the components of a classification:

1. A class is a rational grouping of units that are counted as elements. In textual representation format (graphic format will be presented later), the classes can be notated as follows: //class//. The word "rational" makes it possible to distinguish a class from any random grouping of units.

2. The definition of the class stipulates (1) which feature(s) the elements must have in order to be part of the class; (2) which value these features must take, and (3) the rules for evaluating and determining membership. The definition is what we traditionally call the comprehension or the intension (with an "s") of the class. The features can have three values: mandatory, alternating mandatory (this feature OR else that feature), or optional (but predictable – there is no point in specifying features in the definition that are not very predictable). In textual representation format, the features can be notated as follows: /feature/. The rules for evaluating membership may be simple (e.g., the class is defined by a single, mandatory feature) or complex (e.g., to diagnose depression, at least two out of six symptoms must be present).

3. An element is a unit that belongs to a class. In textual representation format, elements can be notated as follows: ‘element’. All together, the elements of a class form what is traditionally called the extension or enumeration of the class. The features of the included element must match the mandatory features of the class. The element can also have – or not have – one or more non-mandatory features. Since an element has more than one feature (allowing for exceptions), it can belong to more than one class, defined by a single feature or multiple features. A feature may match the name of the class (e.g., the feature /fruit/ for 'apple' in the class //fruit//).

2.2 DISCUSSION

2.2.1 THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN CLASS AND TYPE

What exactly is the difference between a type (e.g., the poetry genre) and a class (e.g., the class of poems)? Strictly speaking, a type is not a class because rather than containing, or bringing together the token units (the poems) governed by it, it generates them. The distinction between a type and the definition, or intension, of a class may seem vague, but they are indeed two distinct things. Type and definition are necessarily abstract entities; token and element can be concrete (this poem as a representative of the poetry genre; this marble as a member of the class of the marbles in this bag) as well as abstract (this love, which is a manifestation of love; humiliation, a member of the class of negative emotions). The difference, then, lies elsewhere. The type is an abstract "individual" that is the result of an induction made from what will become its tokens, relative to which it subsequently acquires the status of a generative entity (as opposed to genetic)1. The definition of a class is not an individual entity, but rather an inventory of one or more properties, optionally accompanied by rules for evaluating the membership of the element. This does not keep us from potentially associating a type with a class.

Furthermore, an element may correspond to a token – a particular wolf in the class of wolves in a particular zoo – or to a type – the wolf as a member of the canine class (along with the dog, etc.).

2.2.2 HOW CLASSIFICATIONS ARE REPRESENTED

A classification – at least if it is simple – may be visually represented in linear textual format, e.g.: wolf < canines < mammals, where the first term is the element (element < included class < including class); animal > werewolf < human, where the element is the term in the middle (class 1 > element < class 2).

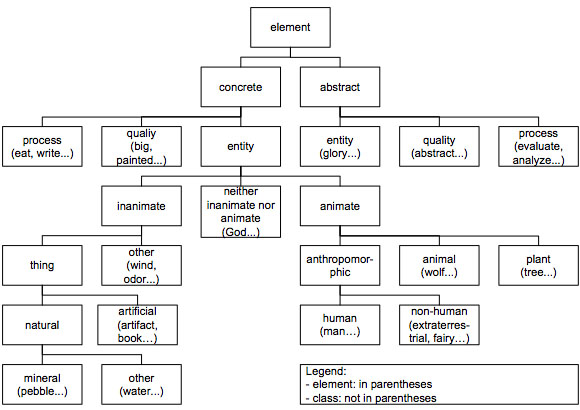

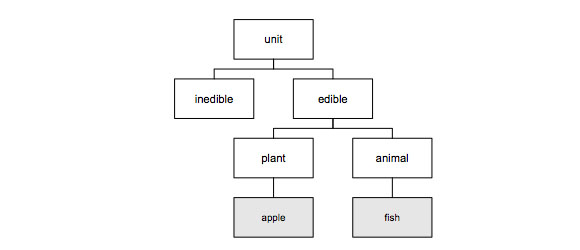

Once it reaches a certain degree of complexity, a classification is usually represented by mapping it out in a strictly visual manner, e.g., with set-notation graphs or a tree diagram. An organizational chart is a tree diagram, but it does not exactly correspond to a classification (for instance, the class //CEO//, which includes the element 'Paul Dupont', does not encompass the class //Marketing Director//, which includes the element 'Pierre Durand'). In a vertical tree diagram, the more specific units are placed below the more general units: an encompassed class appears below the class that encompasses it, an element appears below the least general class to which it belongs (it can also be placed inside the geometric shape representing this class, e.g., a rectangle). Mutatis mutandis for a horizontal tree diagram. Below is an example of a vertical tree diagram. The classes here are the naïve ontological classes (the classes of beings), and the elements are given in parentheses inside the rectangles representing the classes.

The naïve ontological classes

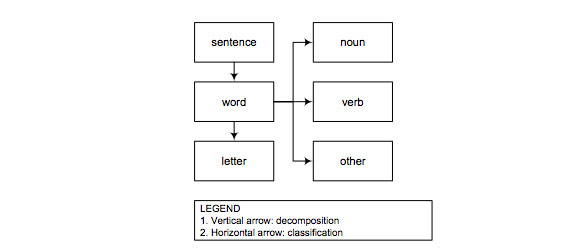

The following convention can be used to visually summarize conceptual networks made up of classes/elements (or types/tokens) and wholes/parts: horizontal arrow: classification operation (the relation between class and element); vertical arrow: decomposition operation (the relation between whole and part). The following is an example of a simple conceptual network.

Example of a simple conceptual network

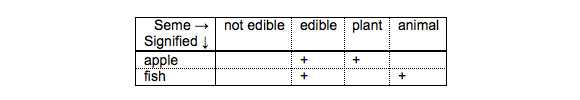

In order to have access to the most effective visual representation, one must be able to convert from a table to a diagram or the reverse. A table may be useful for complex structures, particularly the ones that contain numerous horizontal poly-classifications. Below we give the example of the same very simple structure shown both as a table and as a diagram.

A simple classification represented in a table

Various relations exist between the units of the table. "Apple" is a whole whose parts are the semes (features of meaning) "edible" and "plant"; the same principle applies for "fish" and its semes. Each seme is also the defining feature of a class by that name; this class indexes the units that have the feature as elements: for example, the feature /edible/ defines the class //edible//, which indexes the elements 'apple' and 'fish'. The table shows two aspects of the analysis rather well: a) the descending mereological aspect: it takes a whole (a signified, in this case) and defines the parts (the semes) that compose it (reading across a line in the table); b) the descending set aspect: it takes a class (defined by a seme, in this case) and identifies the elements (the signifieds) that are part of it (reading down a column in the table).

Below is the same structure in graphical representation (the opposition normal boxes/shaded boxes is used to distinguish a class from an indexed element, respectively). It should be noted that the value more general/more specific is apt to vary for the same classes. For example, in this case, one could easily invert the structure and set up //plant// and //animal// as encompassing classes, and //inedible// and //edible// as encompassed classes (so that each encompassing class would have an //inedible// class and an //edible// class under it).

A simple classification represented in a diagram

2.2.3 CLASSES WITH PLUS/MINUS FEATURES AND MONOCRITERIA/ POLYCRITERIA CLASSES

When a defining feature of the class must be present, it can be called a plus feature (e.g., vertebrates must have a spinal column); in the opposite case, it is called a minus feature (invertebrates). If the classification is based on a dyadic categorial opposition (e.g., vertebrate/invertebrate or true/false), the plus feature (vertebrate, true) is identical to the negation of the minus feature (not-invertebrate, not-false; as a counter example, the feature /not-black/ indexes not only the white elements, but also the red, blue, etc.).

A monocriteria class (or simple class) is a class defined by just one feature (e.g., the French textual genre of "formes brèves", in the broadest sense of the term; or the carnivore class). In the opposite case, it will be called a "polycriteria class" (or "complex class"). However, a monocriteria class can presuppose features that come from mono- or polycriteria encompassing classes (for example, the "formes brèves" are literary forms, which are in turn textual forms, which are in turn artistic acts, etc.). In a polycriteria class, all of the features can be mandatory; or all of the features can be alternating, with optionally a minimum number of them present (refer back to the example of depression); or some features can be mandatory and others can alternate with one another (in which case not all the features are weighted the same, since a mandatory feature counts more than an alternating feature).

2.2.4 THE DEGREE OF SPECIFICITY

In theory, one cannot go beyond the degree of precision – the grain, or pixel – of the semiotic act being analyzed. The classification will end where the act ends (although it is possible to indicate the potential classes that are left empty). That is, a text may or may not specify the class of dogs according to breed (e.g., poodle, German Shepherd, etc.). However, by methodological reduction (which is intentional, relevant, and explicitly stated), the analyst may choose to not go as far as the semiotic act (e.g., by stopping at the class of dogs even though the text distinguishes between a poodle and a Saint Bernard). In short, although a class may not necessarily be the most specific one per se, it can be for the semiotic act being analyzed, or for a particular analysis of this act, through methodological reduction.

A semiotic act may create narrower classes than the ones that are generally used (e.g., the class of 19th-century southern Hungarian waltzes!). A semiotic act may create classes of the same generality as the ones that are generally used (in a song, Jacques Brel adds the four-beat waltz and the thousand-beat waltz to the regular waltz, which has three beats by definition).

2.2.5 DISTINCT CLASSES AND DISTINCT ELEMENTS

A distinction should be made between the element or class entity and the name(s) given to it. Two forms of names should be distinguished, since they may not match: the analytical name, i.e., the name given to an element or a class by the analyst (who can simply copy the commonly used names for these entities, of course); and the de facto name, i.e., the name given to an element or a class in the object being analyzed. It would be an error to think that elements or classes are different when they are actually the same element or class designated by different names. That being said, one can merge elements or classes as needed by methodological reduction.

An example will serve to illustrate these problems. In a text, "garbage" and "trash": (1) may be synonymous names referring to one element that is mentioned several times (there is a single rebus entity, sometimes called "garbage" and sometimes called "trash"); (2) may be synonymous names, each used to designate a different element, but belonging to the same class (there are two rebus entities; the first one is called "garbage", and the second one "trash"); (3) may each designate a different element, each belonging to a different class (in this text, garbage is distinguished from trash, even if they are both encompassed elsewhere in an inclusive class).

2.2.6 EXHAUSTIVE/ NON-EXHAUSTIVE AND DECIDABLE/ UNDECIDABLE CLASSIFICATIONS

An exhaustive classification uses all of the elements of the set being described; e.g., for a bag in which all the marbles are black or white, the classes //white marbles// and //black marbles// will be used. A non-exhaustive classification does not use all of the elements of the set being described; e.g., the classes //white marbles// and //black marbles// will be used for a bag that also contains red ones. In the latter case, there is also a residual class (//other elements//), even if it is implicit, where the elements that don't correspond to any of the selected classes are indexed2. Classifications may have different degrees of precision, depending on the number of potential classes that are left in the residual class. For example, the classification: //human//, //animal//, //plant//, //mineral//, //other// is more precise than the classification: //human//, //animal//, //other//.

NOTE: FURTHER DETAILS ON THE RESIDUAL CLASS

The residual class may not be explicitly stated, but this does not mean that the classification structure does not anticipate its existence; it may just be a more sparing approach to analysis. For example, the classes //red marbles// and //black marbles// may be the only ones mentioned, and not the class //other marbles//. In addition, residual classes can be found at various levels in a single classification. To continue with our example, if it so happens that the marbles – no matter what color they are – can have four diameters, but only two are selected, then there will be two residual classes: one for color and one for diameter. So there will be a class //marbles with diameter x// that encompasses //red marbles//, //black marbles//, //marbles of any other color//, a class //marbles with diameter y// that encompasses the same three subclasses, and a class //marbles of other diameters// that encompasses the same three subclasses.

Any property is either decidable or undecidable, and membership in a class is no exception. If the observing subject is not in a position to say which of the proposed classes a particular element fits into, then it is undecidable. If the element can be classified in the residual class, then it is not undecidable.

2.2.7 MONOCLASSIFICATION / POLYCLASSIFICATION

A single element may belong to more than one series of classes. One can distinguish between a "vertical" polyclassification, which includes one or more encompassing classes (wolf < canines (subclass) < mammal (class)), and a "horizontal" polyclassification, which is made at the same level of generality (human > werewolf < canines). The object being analyzed and/or the type of classification used in the act and/or the analysis of this act may allow for only single classifications of a single unit, or may admit multiple classifications. The scientific typologies (e.g., the animal classifications) tend to create single classifications (e.g., an animal is an invertebrate or a vertebrate; it cannot be both at the same time).

2.2.8 CATEGORIAL / INCREMENTAL CLASSIFICATIONS

In an incremental classification, membership in a class is subject to quantification, using a number (e.g., a percentage or coefficient) or a mark of intensity ("not very", "medium" , etc.). An incremental class has an inverse correlation with another incremental class (even if it is the residual class). That is, if someone is less human, he is necessarily more of something else, such as animal. Consequently, we will say that the incremental classes call for horizontal polyclassifications. In a categorial classification, a unit belongs or does not belong to a class; there is no possible quantification. For example, a text may regard a being as human or not, with no middle ground; a marble as red or not, with no middle ground.

2.2.9 MONADIC / POLYADIC CLASSIFICATIONS

A classification may also be characterized in terms of the number of classes it includes; it may be monadic (just one class) or polyadic (dyadic: two classes, triadic: three classes, etc.). The residual class will be included in the count only if it is among the accepted possibilities. For example, for a bag containing only black marbles and white marbles, the classification will be dyadic, since the relevant classes are //white// and //black// (//other color// is not relevant).

2.2.10 ISOMORPHIC / ALLOMORPHIC CLASSIFICATIONS

A classification may be isomorphic (structured identically throughout) or allomorphic (structured differently from one part to another), relative to the various aspects we have mentioned. For example, the number of defining features may be the same for each class or may vary from one class to another; polyclassifications may be possible throughout, or only in certain places; one classification may be entirely dyadic, and thus any class other than a terminal class may be broken down into two subclasses; another classification may include some parts that are dyadic and others that are triadic; one classification may be entirely categorial, while another may have both categorial and incremental classes.

2.2.11 TIME AND THE OBSERVING SUBJECT

In analysis by classification – as in any analysis – the relative variables must be taken into account, particularly time and the observing subject (for details, see the chapter on structural relations). As far as time is concerned, it's a matter of seeing whether the classification changes in response to changes in time: in the indexation of the elements, the characteristics of the classes (defining features, incremental vs. categorial, etc.), the structure of the tree diagram, and so on. For example, the history of physics is punctuated by the discovery of new particles that change the particle classification. Thus, the atom was part of the class of undecomposable elements until it was discovered that it could be broken down into electrons, protons, and neutrons.

As for the observing subject, it's a matter of seeing whether the classification changes based on which agent is taken into account. In a literary text, the observers can be the following, among others: the real or empirical author, the implied author (the impression that the text gives of its author), the narrator, the narratee, the character, the implied reader (the impression that the text gives of its expected and unexpected readers), the real or empirical reader. For example, within one text, the explicit or implicit classification made by a particular character (an assumptive observing subject) may or may not match that of another character (also an assumptive observing subject) or those which the text definitively considers as valid, traditionally through the voice of the omniscient narrator (the reference observing subject). This dynamic between points of view can operate from one semiotic act to another, e.g., in a particular text the reference observing subject views the tomato as a fruit, and in another, the reference observing subject views it as a vegetable. For details on the dynamic between observing subjects, see the chapter on dialogics.

Lastly, one can verify whether the observing subject and the classification are related to a system. For example, an observing subject and a classification that proclaim the tomato to be a fruit reflect an observing subject and classification whose stereotypical sociolect is one of scientific discourse. An observing subject and classification that view the tomato as a vegetable (since it is used in vegetable salads rather than fruit salads) reflect an observing subject and classification whose stereotypical sociolect is one of non-scientific, "naive" discourse. An observing subject and classification that view the tomato as an animal in two texts by the same author reflect an idiolectal observing subject and classification specific to an individual. For details on the various system levels (dialect, sociolect, idiolect, textolect, and analect), see the chapter on structural relations.

3. APPLICATION: "QUELLE AFFAIRE!"3 BY GILLES VIGNEAULT

« Quelle affaire ! » |

"A Sorry Business"4 |

|

| Le lançon l'a dit aux truites | 01 | The sand lance told the trout |

| La truite parle au saumon | 02 | The trout talked to the salmon |

| Le saumon l'a dit au thon | 03 | The salmon told the tuna |

| C'est ainsi qu'ainsi de suite | 03 | And so on down the line |

| De source en lac et ruisseaux | 05 | From spring to lake and stream |

| Tout arrive à la rivière | 06 | It all goes to the river6 |

| Tout passe de sable en pierre | 07 | All is turning from sand to stone |

| Chez tout le peuple des eaux | 08 | For all the people of the water |

| Du fleuve jusqu'à la mer | 09 | From the River to the sea |

| La barbotte et la barbue | 10 | The bullhead and the catfish |

| Étaient à peine au courant | 11 | Had just barely found out |

| Que la sole et le hareng | 12 | When the sole and the herring |

| En parlaient à la morue | 13 | Were telling the cod about it |

| Le capelan, l'éperlan | 14 | The capelin and the smelt |

| Le turbot, le bar, l'anguille | 15 | The turbot, the tilefish, the eel |

| Ont prévenu leur famille | 16 | Alerted their families |

| « Il faut s'enfuir des grands bancs ! » | 17 | "Evacuate the Grand Banks!" |

| Une dame de sottise | 18 | A lady of stupidity |

| Amoureuse des blanchons | 19 | In love with baby seals |

| A promené ses manchons | 20 | Has taken her muff6 |

| Sur le dos de la banquise... | 21 | For a walk on the ice floe... |

| Et notre ennemi commun | 22 | And our common enemy |

| Le phoque de toute espèce | 23 | Any species of seal |

| Qui nous tue et nous dépèce | 24 | Who kills and dismembers us |

| En décembre comme en juin | 25 | In December just as in June |

| Le phoque se multiplie | 26 | The seal is multiplying |

| Et ne craint plus le chasseur | 27 | And no longer fears the hunter |

| Plions bagage en douceur | 28 | Let us gently pack up and go |

| Disait la sole à la plie... | 29 | Said the sole to the flounder... |

| C'est ainsi qu'on ne peut plus | 30 | And that is how it came about |

| Rien pêcher dans le grand fleuve | 31 | That there is nothing left to catch in the Great River7 |

| De Natashquan à Terr'-Neuve | 32 | From Natashquan8 to Newf'ndland9 |

| Le poisson a disparu | 33 | The fish have disappeared |

| Le phoque qui prolifère | 34 | The seal, who is proliferating |

| Un jour crèvera de faim | 35 | Will one day die of hunger |

| À la suite des humains | 36 | After the humans have |

| Quelle affaire ! Quelle affaire ! | 37 | A sorry business! |

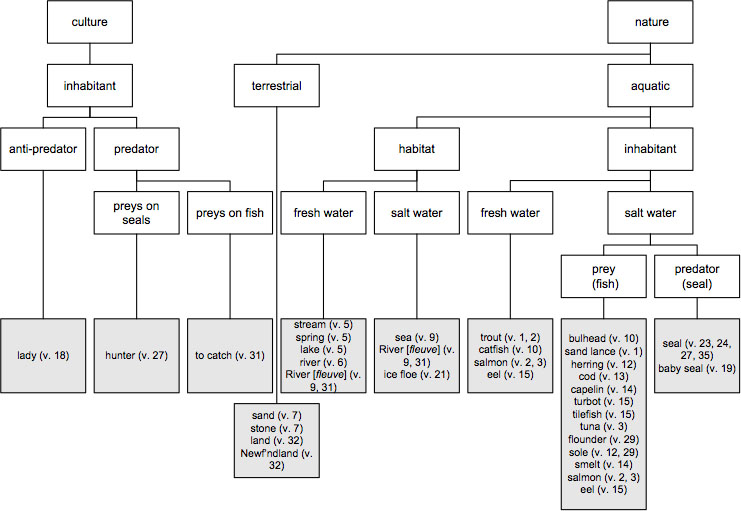

This text by Gilles Vigneault, the famous writer, composer, performer, and poet from Quebec, brings up a political and media affair. In the 1980s, ex-actress Brigitte Bardot, an activist who was opposed to exploiting animals, especially for their fur, denounced the hunting of baby seals in Canada, which led to a sharp decrease in the number of baby seals harvested. The seal population thus increased, and this may have been the main cause – the text supports this notion – or partial cause of the radical drop in the fish populations that seals feed on (as do humans!). Bardot had traveled in person to the ice floes with a film crew. Note the similarities in sound between "Bardot" (a word not found in the text) and "barbotte" [bullhead], "barbue" [catfish], and "bar" [tilefish]. The text uses an interplay of stereotypes: a foreign woman from the city, beautiful but stupid and sappy ("in love with baby seals" (v.19)), comes in and sows chaos in a world she has no understanding of; she profoundly disrupts the natural order she meant to protect, an order which moreover is indiscriminately cruel: The nice baby seals being hunted for their fur are nonetheless efficient at dismembering fish (v. 23-24), but no one is making a fuss over the fate of their victims.

A few remarks:

In the diagram, the opposition normal box/shaded box is used to distinguish a class and an indexed element, respectively. If there is more than one name for the elements indexed in the classes, they are designated by the principal name. That is, the element 'seal' is designated in the various occurrences of "seal", but also in "our common enemy", a name that we do not include in the diagram.

In the anthropological opposition nature/culture, culture refers to anything that is produced by man.

Whenever possible, it is preferable to give identical or comparable names to similar classes, which increases the number of analytical relations. For example, the classes //anti-predator//, //predator//, and //prey// are having a "talk" across the tree diagram from one section (culture) to the other (nature). This allows us to draw a comparison between human predation and seal predation. A parallel can be made between the recursivity of predations (man hunts the seal who hunts the fish) and the recursivity in the transmission of information (fish A tells B who tells C, "and so on down the line").

The classification structure shown here does not claim to be either exhaustive or exclusive. For example, one could distribute the elements in view of the fact that the text is riddled throughout with the opposition little/big, which can be particularized in various ways. It opposes big expanses of water with little ones, big fish with little fish, the seal with the seal pup, as well as collectives with individuals (human and animal collectives and the lady; gregarious/solitary fish), and it even, despite the inversion in the sequence of erosion, opposes stone with the sand it is becoming (v. 7).

The presence of the mineral theme (isotopy) in "sand" and "rock" prompts us to break down the expression "Terr'neuve" [Newf'ndland] to find "terre" ["land"] in it, in addition to the island (Newfoundland) it designates. It can also be read as "Terre" ["Earth"] (the planet), given the far-reaching intention promoted by "the humans" (v. 36), to whom "the people of the water" (v. 8) are replying. Natashquan, an isolated coastal village on the Lower North Shore of the Quebec region, is the birthplace of Gilles Vigneault, and often the explicit or implicit scene of action in his texts. Like Newfoundland, Natashquan is a mediating term (a complex term) between land and sea. And could "sole" be read as "sol" [ground, soil], since we also have "la plie" [flounder], a play on words that hints at others, reappearing as "plions bagage" [let's pack up and go] (v. 28-29)? The opposition land/sea is highlighted by the lady walking on the ice floe (v. 20-21), which is a mediating term in the opposition. Note also the intermediate role played by the seal, an amphibious animal in between fish and humans. Some other plays on words are attestable or plausible: one that indexes the expression "être au courant" [to know about something] in the theme of water [v. 11 literally means "had barely gotten in the current"]; and one that indexes "quelle affaire" (v. 37) [affaire also means business] and the human who "will die of hunger" (v. 35) in the economic theme. (The economic consequences of the Bardot campaign were big).

All of the fish listed here live exclusively in salt water, except the trout, the salmon, the eel, and the catfish [Fr. barbue des rivières]. "Trout" can be taken either as a generic (which encompasses rainbow trout, brown trout, etc.; some of these species are anadromous, meaning that they spend their adult lives in the sea, but ascend the freshwater streams to reproduce), or as a common name for the brook trout (a strictly freshwater fish). We are opting for the second interpretation. The "truite de mer" [sea trout], which is in the Petit Robert dictionary, does not appear in the Liste de la faune vertébrée du Québec (Desrosiers, Caron and Ouellet, 1995). According to the Petit Robert, the "barbue" [turbot] lives in salt water, but only the "barbue des rivières" [channel catfish] is listed in our reference document. We have chosen the second kind of "barbue". Since the expanses of water are listed in increasing order of size from the spring (freshwater) to the sea (salt water), it would be tempting to separate out the series of fish in verses 1 to 3 in the same way. But the sand lance is a strictly marine creature, at least in the document consulted11.

4. LIST OF WORKS CITED

- VIGNEAULT, G. (1998), "Quelle affaire!", L’armoire des jours, Montréal: Nouvelles Éditions de l’Arc, pp. 147-148.

- DESROSIERS, A., F. CARON and R. OUELLET (1995), Liste de la faune vertébrée du Québec, Sainte-Foy (Québec): Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Faune.

5. EXERCISE

Develop a classification for the first two chapters of Genesis.

| 1.1 | In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. |

| 1.2 | The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters. |

| 1.3 | And God said, "Let there be light"; and there was light. |

| 1.4 | And God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness. |

| 1.5 | God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day. |

| 1.6 | And God said, "Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters." |

| 1.7 | And God made the firmament and separated the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. |

| 1.8 | And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day. |

| 1.9 | And God said, "Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together into one place, and let the dry land appear." And it was so. |

| 1.10 | God called the dry land Earth, and the waters that were gathered together he called Seas. And God saw that it was good. |

| 1.11 | And God said, "Let the earth put forth vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees bearing fruit in which is their seed, each according to its kind, upon the earth." And it was so. |

| 1.12 | The earth brought forth vegetation, plants yielding seed according to their own kinds, and trees bearing fruit in which is their seed, each according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. |

| 1.13 | And there was evening and there was morning, a third day. |

| 1.14 | And God said, "Let there be lights in the firmament of the heavens to separate the day from the night; and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years, |

| 1.15 | and let them be lights in the firmament of the heavens to give light upon the earth." And it was so. |

| 1.16 | And God made the two great lights, the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night; he made the stars also. |

| 1.17 | And God set them in the firmament of the heavens to give light upon the earth, |

| 1.18 | to rule over the day and over the night, and to separate the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good. |

| 1.19 | And there was evening and there was morning, a fourth day. |

| 1.20 | And God said, "Let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the firmament of the heavens." |

| 1.21 | So God created the great sea monsters and every living creature that moves, with which the waters swarm, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. |

| 1.22 | And God blessed them, saying, "Be fruitful and multiply and fill the waters in the seas, and let birds multiply on the earth." |

| 1.23 | And there was evening and there was morning, a fifth day. |

| 1.24 | And God said, "Let the earth bring forth living creatures according to their kinds: cattle and creeping things and beasts of the earth according to their kinds." And it was so. |

| 1.25 | And God made the beasts of the earth according to their kinds and the cattle according to their kinds, and everything that creeps upon the ground according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. |

| 1.26 | Then God said, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." |

| 1.27 | So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. |

| 1.28 | And God blessed them, and God said to them, "Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth." |

| 1.29 | And God said, "Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food. |

| 1.30 | And to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food." And it was so. |

| 1.31 | And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, a sixth day. |

| 2.1 | Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. |

| 2.2 | And on the seventh day God finished his work which he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had done. |

| 2.3 | So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all his work which he had done in creation. |

| 2.4 | These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created. In the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens, |

| 2.5 | when no plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up – for the LORD God had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no man to till the ground; |

| 2.6 | but a mist went up from the earth and watered the whole face of the ground – |

| 2.7 | then the LORD God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being. |

| 2.8 | And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed. |

| 2.9 | And out of the ground the LORD God made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food, the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. |

| 2.10 | A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers. |

| 2.11 | The name of the first is Pishon; it is the one which flows around the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold; |

| 2.12 | and the gold of that land is good; bdellium and onyx stone are there. |

| 2.13 | The name of the second river is Gihon; it is the one which flows around the whole land of Cush. |

| 2.14 | And the name of the third river is Tigris, which flows east of Assyria. And the fourth river is the Euphrates. |

| 2.15 | The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. |

| 2.16 | And the LORD God commanded the man, saying, "You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; |

| 2.17 | but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die." |

| 2.18 | Then the LORD God said, "It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper fit for him." |

| 2.19 | So out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name. |

| 2.20 | The man gave names to all cattle, and to the birds of the air, and to every beast of the field; but for the man there was not found a helper fit for him. |

| 2.21 | So the LORD God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and while he slept took one of his ribs and closed up its place with flesh; |

| 2.22 | and the rib which the LORD God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man. |

| 2.23 | Then the man said, "This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man." |

| 2.24 | Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and cleaves to his wife, and they become one flesh. |

| 2.25 | And the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed. |

1 We will give a simple example of generative and genetic viewpoints: If we isolated the world view governing the production of a work of literature, we would be isolating a hypothetical, abstract form that generated the work; if we studied the notes and the rough drafts for this

2 Even when one thinks that the classification is exhaustive and that it covers all the units to be described, it may be wise to provide a residual class "just in case" some units were inadvertently neglected. The neutral term of a semiotic square might seem like a residual class for a classification that is both dyadic and oppositional, but the potential residual elements must be checked to ascertain that they actually do represent the negation of the two basic oppositions of the square. For example, in the semiotic square wealth/poverty, "tomato" does not fit under the neutral term (it is simply a unit external to this square), but "middle-class" does. For details, see the chapter on the semiotic square.

3 Translator’s note: “Quelle affaire” is a common expression meaning “what a fuss”, or any of a dozen other equivalent expressions.

4 Translator’s note: This English translation is given only to explain the poem’s meaning. It is not itself a poem, and would never be published as such.

5 Translator’s note: “River” is capitalized here to distinguish Fr. “fleuve” from Fr. “rivière”. The former is a river flowing into the ocean, and the latter is a river flowing into another river.

6 A muff is a cylindrical cover, commonly made of fur (the Petit Robert gives the expression manchon en fourrure... [fur muff]), in which the hands are placed for warmth.

7 This "Great River" is obviously the St. Lawrence, which contains salt water downstream from Québec city, and especially from Natashquan on down to Newfoundland.

8 Natashquan: a town on the north bank of the St. Lawrence where the author was born.

9 Newf'ndland: Newfoundland, an island and Canadian province east of Québec.

10 We are expanding a classification originally proposed by two students, Ariane Voyer and Marie Amiot.

11 Translator’s note: The Petit Robert is published in France. Since Vigneault is from a fishing village in Quebec, he is using the local name for each fish, which does not match the European name in many cases.